Trip Report by Caleb McIntyre

Cover Photo Credit: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Preface

Some of us are lucky enough to travel when we’re still young, dumb, and reckless.

I was one of those people.

Fed up with my early career choices, drunk on wanderlust, and inspired by books I’d read about the ‘beat generation,’ I took off from the liberal paradise of my coastal homeland in British Columbia only to eventually find myself lost in Nicaragua - both physically and spiritually - as I wandered, wondered, and waited for a good enough reason to go back home.

If you’ve ever done something similar, you can probably relate. Trips like this tend to yield intense connections with total strangers. They teach us about the power and potential of humanity. They expand our ideas of who we are. On a personal level, that first solo travel experience helped me understand my privileges as a self-identifying 'white trash' Canadian, and gave me a glimpse into what community really means, why it matters, and why I should try to bring it back home.

But this story isn’t about that trip. It’s about 10 years later.

Above: wandering the shore of Lago Colcibolca back in 2015.

Fast forward to the recent past. It’s late 2025. I’m a father, a die-hard community member, and director in a global paddlesports company. While I no longer feel lost in the spiritual sense, I do find myself with a mortgage to pay, mouths to feed, and investors to please. What I want to do is rarely top of mind anymore.

Needless to say, my inner child often feels starved these days. It’s as if part of my spirit is still in Nicaragua, wondering what happened to that long-haired hippy with his life in a backpack. I find myself reflecting on how easy life used to be; how simple things were when I was solely focussed on meeting my daily needs of food, water, shelter, and companionship. I miss the ease and nonchalance with which I used to conduct my daily life. Sometimes I miss being just… me.

It was around this time, in fall 2025, when I reckoned I was due for a proper adventure, once again.

A Gift from the Universe?

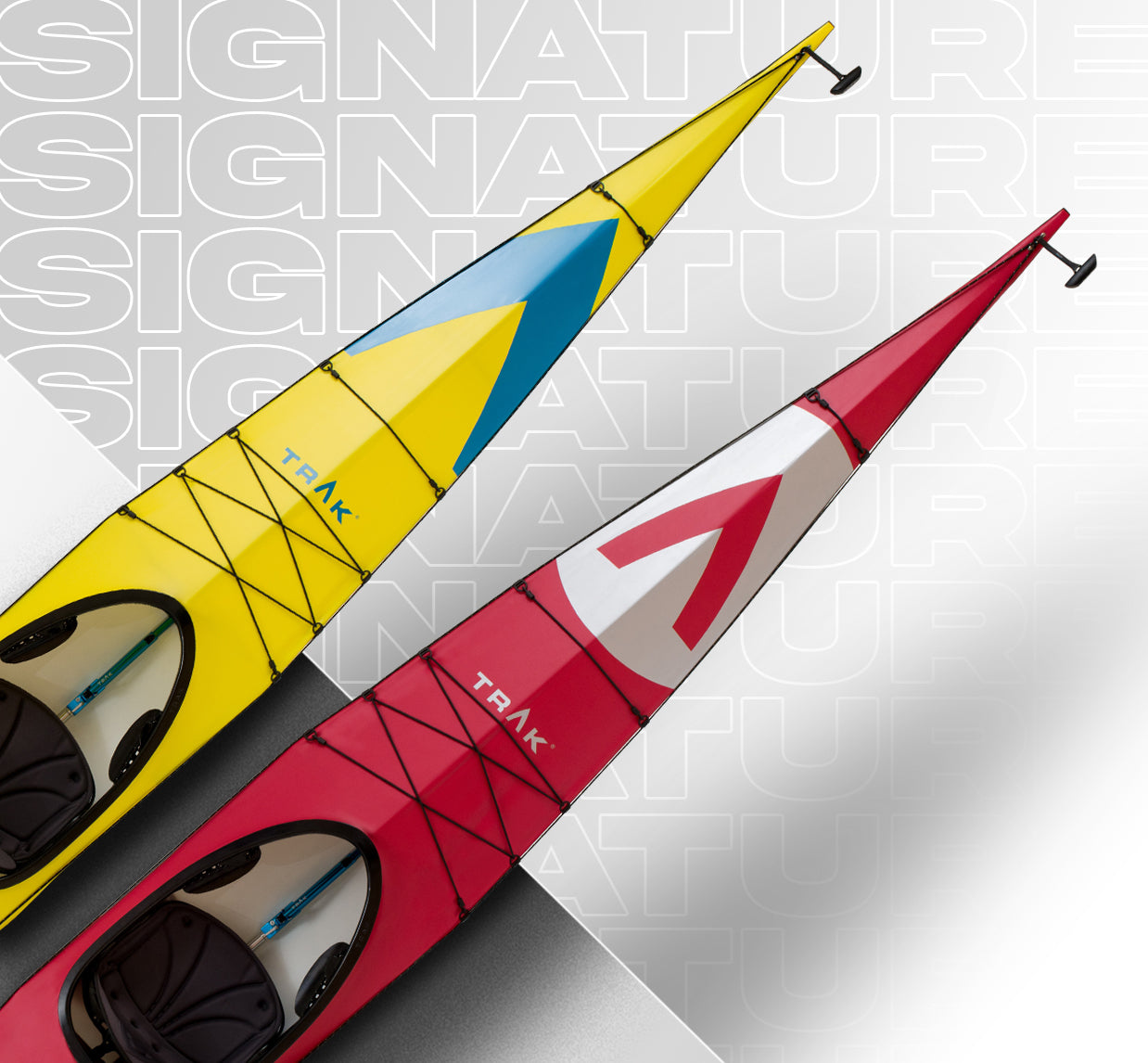

Soon after this realization, I sat down at my desk at TRAK HQ and opened an email from Jim Mee at Rat Race Adventures - a UK-based events company that specializes in what they call ‘extraordinary adventures for ordinary people.’ Jim and his team had a bold idea (which they have often): they wanted to cross Nicaragua entirely by human power through a combination of hiking, biking, and (mostly) kayaking. They had the right team and logistical expertise to pull it off - but they still needed to find proper seaworthy kayaks that could be flown in for the mission. Hence why they reached out to TRAK.

Rat Race’s proposed mission in Nicaragua was ambitious: hike to the country’s highest point, bike to the Pacific Coast, continue pedaling to the west coast of Lago Nicaragua (a true inland sea), and then paddle south and east across the massive lake, into the San Juan river, and spill into the Caribbean. In just 16 days. No problem, right?

I’ve always been drawn to ‘hard things.’ I like pushing limits, challenging assumptions, proving myself to myself.

Perhaps this is why it took exactly 0.5 seconds for my youthful wanderlust to jump back into full gear after meeting Jim over a video call.

I felt it all: desire, nervousness, jealousy, fear, nostalgia. I wanted to experience real adventure again. And I wanted a chance to put TRAK kayaks to the ultimate test in an outfitter context. But this trip wasn’t for me…

Until it was.

With a mere four weeks to go before Rat Race’s trip launched on Dec 1, 2025, Jim reached out and told me he wanted to acquire enough TRAK kayaks to make the trip possible. To put a cherry on top, he asked if I wanted to join the trip and provide in-field support to ensure everything went smoothly with their fancy new fleet of TRAKs.

I immediately purchased my flights. No hesitation. As far as I was concerned, the universe was answering my prayers, and I could ask my boss for permission and my wife for forgiveness later.

And then amazing things started to happen. Nolin, TRAK’s founder, immediately supported the mission. My wife, Terra, said “okay” and agreed without complaint to be a single parent for the 18 days while I was away. And my team at TRAK really stepped up, agreeing to cover the majority of my daily tasks while I represented us abroad.

It was happening. Exactly one decade later, I was going back to Nicaragua. Woah!

Getting there…

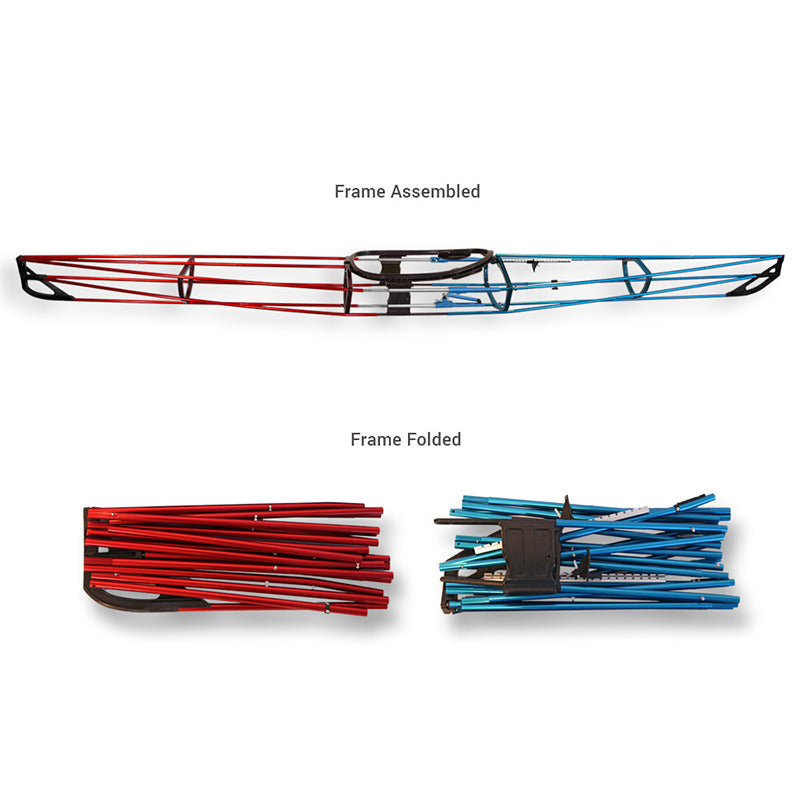

One of the hardest parts of the journey was figuring out how to get myself, three TRAK kayaks, and 10+ days worth of calorie-rich snacks and rations into Nicaragua. I spent multiple evenings with a digital scale, weighing every piece of kit in order to determine what to bring and what to leave behind.

To simplify my journey with multiple TRAK kayaks, I decided to splurge on a 70lb / 32 kg limit, rather than the standard 50 lb / 23 kg limit. This allowed me to travel with literally all over my paddling equipment in a single TRAK rolling bag, including PFD, throw rope, bilge pump, repair kit, and my Solstice King Greenland paddle - plus extra paddles, water filtration equipment, and spare parts in the other TRAK bags. Check-in in Vancouver (YVR) was actually a breeze, and while I was directed to load my kayak bag in the oversize/overweight area, I was not hassled or questioned about the contents of my bags in any way.

This was not the case upon landing.

18 hours later, I landed in Managua, the urban capital of Nicaragua. It was around 11pm local time on the evening of Nov 30th. I'd already been up for over 18 hours. I collected my bags from the carousel - which included two additional new TRAK Kayaks that I had brought down from Vancouver Island - and proceeded to customs. Having never seen a folding kayak before, the Nicaraguan customs officials immediately flagged all three rolling bags for inspection based on their perceived newness and high value. Recognizing that these folks would probably want to charge me import duties, I struggled in my broken Spanish to convey that the kayaks were not for sale, to no avail. The officials took the bags into their possession and told me to come back in the morning. I was in a totalitarian state, and I had to play by the rules.

Above: waiting alongside Nicaraguans who have to pay to have their imported items released from customs officials

Above: waiting alongside Nicaraguans who have to pay to have their imported items released from customs officials

Nearly two hours later, my friend and colleague from Panama was facing similar hangups at airport customs. Founder of Jungle Treks, Rick Morales and I met at the 2025 TRAK Owners Gathering on Saysutshun back in September 2025, where he picked up his own two TRAK kayaks. As one of Rat Race’s leading liaisons in Latin America, Rick’s trust in TRAK is one the reasons this trip moved forward at all.

Above: reclaiming our kayaks from Nicaraguan customs after several hours of waiting (and praying)

Over the next 12 hours (including a brief rest at a nearby hotel), Rick and I got to know each other quite well as we worked our way through Nicaragua’s customs bureaucracy. As a native Spanish speaker, Rick managed to sweet talk our way into a ‘temporary import’ status for all of our TRAK kayaks, allowing us to reclaim our boats (for free!) and join the rest of the Rat Race test pilot team before the end of day on Dec 1st.

The first challenge was complete, and we hadn’t even started paddling yet!

Our kayaks accounted for, we drove north to meet up with the rest of the Rat Race team in Ocotal, the launch point for our human powered mission.

Launch

Day 1 of our human powered mission kicked off with an intense multi-sport challenge: first, hike to the summit of the highest peak in Nicaragua - called Mogoton - then bike from the base of the mountain as far south and west as possible before dark, en route to the Pacific (several hundred kilometres away).

The route to the top of Mogoton is not well trodden. Located on Nicaragua’s border with Honduras, this region is far away from the gringo tourist trail, and is still riddled with land mines and unexploded ordinance from Nicaragua’s civil war between the Sandinistas and Contras in from 1978 to the 1990s.

Above: Trekking to the high summit in Nicaragua. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: Trekking to the high summit in Nicaragua. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

So we stuck closely behind our local guide, Stefan, and never deviated from the prescribed route. A cloud forest in the literal sense, there was no view at the top of Mogoton, but by the time we returned to the base of the trail, the camaraderie within our group was firm. We took turns carrying our medic’s excessively large bag, while simultaneously adjusting to the heat, humidity, and challenging terrain that is found in this part of the tropics.

Above: A partially uncovered landmine, a few feet from the trail.

Time to ride!

Biking has long been my favourite outdoor activity (next to paddling). Alas, one of the biggest ‘unknowns’ for us on this trip was the status of the bikes that Rat Race was able to procure from local outfitters. As a developing country with a growing eco tourism sector, Nicaragua is no stranger to adventure-hungry gringos, but as far as we knew at the time, no other group of outsiders had ever attempted this kind of human-powered nation crossing expedition before. And while the TRAK kayaks we had brought into the country were certainly high performance, we could not say the same for the bicycles available for hire there.

Ranging in era from the early 2000s to late 2010s, most of the bikes available offered mechanical disc brakes and well-worn gravel tires, but lacked the kind of regular maintenance and upgrades that would be expected in Canada or the UK. Regardless, we geared up, donned our helmet and padded shorts, and prepared to send it!

After descending the rest of Mogoton on two wheels - often riding straight through knee-deep rivers along the way - we joined mainstream vehicle traffic on the rural roads of northern Nicaragua, passing through small villages along the way. But with daylight dwindling, and the roads narrowing, it soon became too dangerous for us to continue without posing a risk to ourselves and motorists travelling in both directions. So we called it for the night, hunkered down in a hostel intended for travelling workers (not tourists), and did our best to fix the various mechanical problems that had arisen throughout that first day.

Plan A to Z

It was at this time that we had to debate our first route change. While we had originally hoped to bike from Mogoton to the west coast, it was already clear that these aged two-wheeled machines were not going to get us there within our allotted time frame. For instance, my own bike had a faulty hub on the rear wheel that made pedalling feel slow and extra tiresome, even when going downhill. There was no way I would be able to ride over 100 miles a day for four days on that beautiful old beater…

So, staying true to our intentions, we modified our route to maintain the human-powered element of the trip, though with slightly less distance to cover in total.

Above: my two-wheel (not so trusty) steed for this adventure.

Above: my two-wheel (not so trusty) steed for this adventure.

On Day 2, we mounted our two-wheeled steeds once again, this time at a much lower elevation and at a much higher temperature. With the bikes being best suited for off-road and gravel, we chose a more scenic route that would keep us off the highways (for the most part) and provide a more authentic reflection of rural Nicaragua - complete with washouts, garbage dumps, pigstys, and plenty of cute kids waving as we rode by.

With dust masks over our months and noses, we pedalled south at a strong and steady pace, eventually skirting the base of Volcan Mombotombo - which last erupted in 2016. With sweat dripping from my face all day, it was tricky to keep the sunblock on, but I refused to let myself be compromised by sunburn. Hydration and electrolyte consumption was key - and we never let each other forget it!

What made this day so special was who we shared the roads and paths with. Very few people own cars in these parts of Nicaragua - they’re simply too expensive except for the most wealthy locals and expats. Instead, locals get around on foot, horseback, and - like us - by bicycle.

All complaints about the mechanical issues associated with our rental bikes were thrown aside when we saw how those rural Nicaraguans commute on two wheels. Their bikes are often single speed, lacking brakes or suspension of any kind, and yet our group was passed multiple times by local riders on their way to work, often with a shovel or pick over their shoulder, or a machete mounted precariously on the frame.

This was just one of many occasions when the aspirations of our ‘grand adventure’ were subtly jested by the realities of daily life in this small, poor Latin American country. What seemed daring and bold to us was really just another commute for these locals. And what we might dream of doing just once is something they might do literally every day. It was humbling to say the least…

Foreshadowing

After reaching the shores of Lago Managua late that same afternoon, we caught a glimpse of what was to come during the upcoming paddling segments of the trip. This lake is about half the size of Lago Colcibolca - which we were set to cross in the days ahead - but with strong winds whipping down from the sides of Volcan Mombotombo, the sea state on the lake was fierce, with whitecaps everywhere. As we stood there, taking stock of the ground we’d already covered, the thought of paddling into those tropical headwinds day after day for many hundreds of kilometres felt incredibly daunting. All we could do was hope and pray for calm conditions when we reached Granada in two days time. Fingers crossed…

By the end of Day 2, we settled into the youthful city of Leon (resettled after Volcan Mombotombo erupted in 1610), and our group prepared for what would surely be the longest and hardest cycling day of the trip. On Day 3, we would start our journey from the Pacific Coast, over the continental divide, and into the historical colonial capital of Granada - our launch point for the TRAK fleet on the northwestern shore of Lago Nicaragua.

Above: a quick 'rinse' in the Pacific Ocean before we head east.

From the Pacific...

As expected, that final day of riding was tough, but it was also one of the most beautiful, memorable, and rewarding days of cycling in my life.

From the shores of the Pacific, we said “buenas dias” to several fishermen returning from their early morning catch and began our long ascent into the volcanic mountain range that separates Nicaragua’s two main watersheds. We rode through cane sugar fields, crossed multiple rivers, and passed through a seemingly endless series of remote villages connected only by off-road vehicles. When locals saw us riding through their little towns in our lycra and high performance gear, they would often point and laugh, as if to say “What the heck are you doing here! You’re crazy gringos!” Some would simply stop and stare, confused as to why a group of tourists would want to visit their humble corner of Nicaragua. One journalist even stopped and interviewed us about our mission, sharing that foreigners are rarely seen in that particular corner of the country. Each day, we were a spectacle - that’s for sure!

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Occasionally, we would emerge from the forest onto paved and cobbled roads, passing through city centres marked with the classic Latin American plaza with a Catholic church or cathedral at its head. In places like this, we’d stop for a quick break, chug cold Coca-colas and slam back whatever sugary snacks we could get our hands on. There was never time for lengthy lunch breaks on this trip, so we got really good at surviving on handfuls of chips, empanadas from cart vendors (if we were lucky), and assorted granola bars and fruit snacks that I’d brought from Canada. The little things go a long way on days like this, so I was really glad that I brought my favourite snacks from home, as Nicaragua tends to lack high protein and nutrient rich snacks.

Above: overlooking Laguna Apoyo, our highest point of the day

Above: overlooking Laguna Apoyo, our highest point of the day

After biking uphill for around seven hours, we reached our highest point for the day atop Mirador de Catarina, which overlooks the giant volcanic crater known as Laguna de Apoyo. With Granada and Lago Nicaragua on the horizon, the sheer scale of our adventure finally presented itself visually. There is no visible shore on the far side of Lake Nicaragua - from Catarina, it looked just like an ocean…

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

My bike was really starting to fail me at this point; in particular, the hub was giving out once again, and keeping up with my teammates was getting increasingly difficult. Luckily, the end was in sight, and it was all downhill from here. With our group in high spirits, we rallied to the finish, reaching the shores of Lago Colcibolca - Central America’s largest lake - just before nightfall. With hugs and high fives all around, we celebrated a proper tourist trap restaurant and shed our bike gear once and for all.

We were done with the biking component, but this trip across Nicaragua was really just getting started…

Above: An unusually calm evening on Lake Colcibolca. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: An unusually calm evening on Lake Colcibolca. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

On the water, finally!

The following morning, select members of our team returned to customs offices in Managua to complete the ‘temporary import’ process for the last three TRAK kayaks that were flown in from the UK. Thanks in part to the quality time Rick and I spent there upon our arrival, we seemed to gain the favour of a senior customs official who wanted to see our team succeed, and luckily our last batch of kayaks were released with minimal hassle.

Assembling the TRAK fleet at the northern shore of Lago Colcibolca

Assembling the TRAK fleet at the northern shore of Lago Colcibolca

Contrary to what had been promised by local vendors, there were simply no seaworthy kayaks in the country capable of crossing Lago Nicaragua. So, to fill the gaps in our fleet, the Rat Race team arranged to rent two plastic 16’ OldTown hardshells from an American expat in Granada. These would be slower on the water than the TRAKs, but at least could handle the conditions without added risk - and they were already here, ready to go.

Just in time, we had a complete fleet of kayaks, ready for assembly on the shores of Lago Nicaragua!

At this point, we made contact with our local guides for this portion of the expedition. Considering the novelty and risk involved in this particular segment of the trip, Rat Race chose to hire two support boats, with local crew, to ensure that we always had an exit strategy in case conditions on the lake exceeded our team’s capabilities. Unlike myself, most participants on this trip were not experienced sea kayakers; but what they lacked in technical knowledge they easily made up for with sheer enthusiasm and grit. There were no quitters in this group, that’s for sure! We had no intention of bailing out, but we still needed local knowledge to find our way and secure safe landing zones in advance - especially since no one had ever paddled this route before.

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

After assembling all our TRAK kayaks on the shore, we joyously took to the waters and began getting familiar with our boats. For me, it was a real treat to see each of my teammates get comfortable with their new high efficiency water vehicle, and we spent some quality time to optimize each paddlers’ placement of foot braces, thigh braces and back bands for the long haul ahead. We also spent a couple hours building foundational paddling skills amongst the picturesque Las Isletas de Granada, gradually emerging from the protected archipelago into the open waters of the lake.

Despite its classification as a lake, Lago Nicaragua behaves like an inland sea, with huge fetch delivering ocean-like swell, steep waves, and rapidly changing conditions that can catch you off guard. Add the fact that much of the lake offers no safe or suitable place to land a kayak, and you’ve got the recipe for serious (mis)adventure.

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

We got a strong taste of these factors on Day 4 of the trip, especially when it became clear that we wouldn’t make our intended destination for the evening. With daylight fading fast, we selected an alternative ‘plan B’ landing zone: a beach that ended up belonging to a few very poor but very gracious farmers who welcomed our group to make camp for the night.

As we turned into a narrow bay to land, the wind and waves started converging, stacking up and combining into larger, steeper rollers. As a sea kayak guide acting in a supporting role, I tend to drop back at times like this, following more novice paddlers in case things go south. I was glad that I did in this case, as one of our team members capsized twice in the process of paddling to shore with surfy following seas. This was a great opportunity to practice my rescues skills, but also a great opportunity to support this teammate with more advanced technical paddling. In situations like this, with tight wave periods and very steep conditions, sometimes the best thing you can do is relax, let the boat do the hard work, and simply keep your paddle in the water, always ready to brace. Watching a very strong individual capsize their kayak by simply ‘trying too hard’ was a big reminder of the nuances of paddling, and how important it is to slow down even when everything around us seems to be picking up in intensity.

Above: storm clouds roll in, and it's time to get off the water! Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: storm clouds roll in, and it's time to get off the water! Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Once safely on shore, we were all thankful to have any place to crash for the night. While some of us claimed trees for our hammocks, others had to setup using the shanty wooden structures of our generous hosts, including a ‘front porch’ space and even a grounded boat. I made a fire that night to boil water for my dehydrated meal - a cheesy pasta that hit just right - and settled into bed extra early to make up for all the late nights and early mornings that had come before (including those at home). As a father of a toddler, I admit to feeling sheepishly guilty about getting so much sleep that night. While I rested soundly in my hammock, my partner was singlehandedly handling our son back home… This was just one of many instances of ‘Dad guilt’ that I felt during the trip, but it was something I learned to let go of in favour of relishing the experience to the fullest.

The next day (Day 5) came extra early. We needed to make up for lost time, and cover nearly 50% more ground/water than initially planned. While it’s not uncommon for smaller groups of experienced kayakers to plan distances of 30km+ per day, it’s quite rare for larger groups of novice or intermediate kayakers to set these same goals. But Rat Race adventurers are a special breed, and so we set off with an ambitious objective to reach the large volcanic island in the middle of Lago Colcibolca - Ometepe - by end of day.

Ometepe will always hold a special place in my heart and soul. I first travelled there as a thin-bearded twenty something exactly ten years prior - and I almost got stuck there. The pace of life on that island is perfectly slow, the people seem perpetually content, and the natural beauty of the place helps explain at least partly why. The south side of the island is an ancient volcano, known as Maderas, while to the north lies a much younger and taller volcano, known as Conception. Joined at the hip to form a single landmass, these adjacent volcanoes offer a unique balance of youthfulness and wisdom, masculine and feminine, freshness and decay. The map of the island feels like something out of a video game designer’s brain, and yet the very self-sufficient nature of the island makes you feel as if you never need to leave. In fact, I think some locals never do. It has everything I could ever want or ask for.

Hiking up the side of Vulcan Maderas back in late 2015.

Hiking up the side of Vulcan Maderas back in late 2015.

But crossing the minimum 16km of open water to Ometepe is no small feat. As far as our local guides are aware, no one - not even locals - have attempted to paddle the distance from the mainland to Ometepe since pre-contact with Europeans. While we did see one makeshift sailing rig on a small fishing boat at one point, most of the boat traffic on the lake is made up of small fishing skiffs, usually with a 30-60 hp outboard, and a large diesel powered ferry makes the journey twice a day for locals and tourists. The idea of paddling far from shore is unheard of here, and when I ask our guides if they think we’re un poco loco (a little crazy) for attempting this crossing, they don’t hesitate to laugh and admit that they think we were nuts.

Reflecting on the conditions we witnessed on Lago Managua back on Day 2, it was always reasonable to predict that the crossing to Ometepe might not be possible, at all. Considering the amount of fetch here, if the winds increased over 15-20 knots for any amount of time, there was a very real chance that even the strongest paddlers amongst us would not survive the ordeal. The sea state could turn into a nightmare, and simply staying upright would become a struggle out there.

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Mid-way through Day 5, after our only substantial break (we usually only took 2-3 land-based breaks each day, sometimes less), we were prepared to make a ‘go-no-go’ decision. Initially, it seemed most of the group was leaning towards ‘calling it,’ accepting our fate, and giving up on the idea of even attempting such a bold and committed crossing. But as we donned our PFDs and spray decks after our ‘lunch’ of snack bars and chips, something miraculous happened…

Through some divine providence, the winds began to subside, and so did the sea state. Whereas previous days had thrown a seemingly endless onslaught of waves on our portside beam, the lake now started to mellow out, threatening to go almost glassy.

Little conversations amongst paddlers and guides started breaking out. “Should we go for it?” “This might be our only chance?” “Let’s see if the others are down to make the push.”

In a matter of minutes, every one of us was of the same mind. This is what we came for: to do hard things; perhaps even things no one has ever done before. If we can do it safely, why hold back now?

I’ll never forget this moment in my life as a paddler; I got the sense of charging (as if into battle) with my teammates across that lake. We’d already paddled nearly 30 km at this point, and yet the realization that we were doing this - paddling to Ometepe, a place of dreams, a place of my youth - was all I needed to refill my metaphorical gas tank and send me on my way to victory, regardless of the grind and pain ahead.

Above: the first crossing to Ometepe. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Two hours later, and it felt as if we’d made absolutely zero progress. Sure, behind us the shore was far away, but the towering peak of Volcan Conception still looked no closer than it did from the mainland. This was the true test for us, mentally and physically: to keep going, believing that we would make it before dark.

It would take nearly over four hours of non-stop, trance-like paddling to reach the distant shore. The wind stayed in our favour the entire time. At one point during the crossing, one of our local guides - all of whom are used to seeing this part of the lake fraught with wind and waves - asked us what saint we had prayed to for safe passage. And while one participant made the wise decision to bail out part way across due to a shoulder injury, the rest of us made it self-supported.

By the time I stood up on the sandy shores of Ometepe, with a cold beer pressed into my swollen hands and the sun low on the horizon, we had paddled nearly 42 km, including a 16 km non-stop crossing from the mainland. It was the longest day of flat water paddling I’d ever done, and the longest crossing I’ve ever even considered. Of course, this record was set to be broken only mere days away…

Above: celebrating our successful crossing to Ometepe. From left to right: Luke, Kat, Rick, Jim, Dovey, Darren, Budgie, Caleb, James, Stuart, Paul. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: celebrating our successful crossing to Ometepe. From left to right: Luke, Kat, Rick, Jim, Dovey, Darren, Budgie, Caleb, James, Stuart, Paul. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

As expected, Ometepe did not disappoint. We slept that night at arguably the most beautiful accommodations of the trip; a far cry from some of the hostels and bushcamps we’d stay at in days to come. But our bodies were far too tired and sore to stay up and relish in the full moon, and I recall falling asleep almost immediately upon hitting the pillow.

On Day 6, we woke early the next morning to the sounds of howler monkeys in the canopy above us. We drank black coffee, ate a typical Nicaraguan breakfast, and prepared to pick up from where we left off the evening before.

Paddling along the protected southern shore of Ometepe was a blissful respite from prior days, not only because of the gorgeous natural scenery, but also because of a break from the wind and waves that come across the length of Lago Nicaragua.

While stationary floating objects tend to get pushed parallel to waves and winds (think of floating logs in the waves), moving watercraft tend to get pointed into the wind and waves when taking those forces on the side (or ‘on the beam’). This is what sailors and paddlers refer to as weather cocking, and it’s something we really had to get used to on this trip. It’s a helpful trait when paddling into the wind, but trying to paddle perpendicular to the direction of the wind tends to require repeated sweep strokes on the windy side, paired with occasional rudder braces on the lee side.

But with the shore on our left nearly all day, we covered ~25km with ease and were able to stop for several scenic breaks along the way, including at a beachside bar for locals that I remembered visiting ten years prior with friends! What are the chances?!

Above: regrouping after a short break at a lakeside bar on Ometepe. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: regrouping after a short break at a lakeside bar on Ometepe. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Day 6 was a relatively short day in the context of this expedition (only 25km compared to 41 the day before), and I remember feeling surprisingly strong and more confident than I had expected to. Leading up to my departure, I wasn’t able to train for this trip as much as I would have linked to, but I was glad to discover that my endurance levels have remained strong despite my newfound ‘Dad life’ routines (or lack thereof). A bit of yoga throughout the last decade, which I started learning ten years ago here in Nicaragua, has undoubtedly helped too. Regardless, it was rewarding to be able to keep up with my colleagues on this trip - all of whom are in very good physical shape and were absolute senders out there. No complaints from these folks - only excellent, well-timed humour!

Then came our toughest call on the trip.

When the wind decides

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

When looking at the original route plan, the most glaring question mark lies in the paddling segment between Ometepe and the Solentimane Archipelago at the southern end of Lago Nicaragua. It’s a huge gap, with us paddling into seemingly…. nothing? Well, turns out there are small pieces of land in the middle of the lake - small enough to be called islets - but very little is known about them, and they rarely appear on satellite images. Local guides informed us that fishermen sometimes anchor their boats in the lee shore of one of these islands, called Zinote, to wait out storms. But other than that, we had no beta on what to expect when we got there.

If we could get there…

By Day 7, our luck with the weather was starting to run out. After a couple days of unusually light winds, forecasts were calling for a return to strong easterlies, giving us reason to expect that even if we could cross to Zinote, we might be stuck there for multiple days afterwards. Furthermore, with no beta on the landing conditions or even the availability of trees for our hammocks, the risk of paddling 30+ km out into open water - without initial visibility of our destination - was starting to become too high for this particular group, especially with our limited timeline.

So, in keeping with the goals of the expedition, we decided on a shorter, more achievable crossing back to mainland Nicaragua from Ometepe - just 22km of open water. From there, we would shuttle by fishing boat to the shelter of the Solentiname Archipelago (part of our intended route), and wait out whatever storm was coming for us before and continuing on to the mouth of the San Juan river.

Above: taking in the sheer distance to cross back to mainland Nicaragua. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: taking in the sheer distance to cross back to mainland Nicaragua. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

I admit, while part of me was disappointed, another part of me was relieved to know we’d finish the trip on schedule. And, the return paddle from Ometepe on Day 7 was beautiful, with both of her volcanoes gradually receding behind us as we crossed Lago Colcibolca over the next five hours, non-stop. By this point, I was getting good at taking advantage of short breaks to exit my kayak, stretch my legs, cool down in the water, and have a good pee break before cowboying back in. For me and my tiny bladder, these brief exits felt absolutely necessary after 3+ hours in my cockpit, and gave my tight hips a much needed respite.

A Quick Detour

Upon reaching the distant shore, the time came for us to start packing down our TRAK kayaks for transport. We selected a patch of long grass in favour of sand, lined up our boats, and packed them up into their rolling travel bags over the next few minutes. Like magic, our entire fleet of nine TRAK kayaks was packed into the back of a pickup truck in less than 30 minutes.

An hour later, we were motoring past the tiny islet they call Zinote. It appeared to be a single large rocky mass, with a few lean trees leaning off the side. No flat ground. Limited options for hammocks. Sharp rocky shores. Karst everywhere - the worst ground for kayaks of any composition. It would have been a disaster to hide out a storm on an islet like this, surrounded by a minimum of 30km of open water. We made the right call to forfeit our plan A (at least this time around).

Arriving in the Solentiname Archipelago felt like something out of Jurassic Park. Virtually untouched by modern civilization, there is very little evidence of human impact amidst this densely vegetated chain of islands. The few folks who do live here stick mainly to the flatter islands, where land has been cleared for farming and small villages have formed around the few safe harbours protected from the trade winds. Numerous petroglyphs hidden through the islands demonstrate that humans have been residing amongst these isolated islands for millenia, harkening back to a time when humans did cross this lake (entirely) by human power.

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Finally, a rest day was ordered on Day 8 - if only because the winds said so. We relaxed in the one family-owned tourist accommodation in Solentiname, operated by our guides Laureano Mairena and his brother Eduardo - sons of a Nicaraguan revolutionary martyr.

The setting was magical. Rains came and went all day long, with exotic birds chirping and nesting in the flowering trees surrounding us. I went for a short walk to explore, but otherwise enjoyed a full day off.

For the next few days, we would see pictures of Laureano and Eduardo's father displayed at each military checkpoint on the San Juan river...

For now, we simply relished the opportunity to be guests, lay in hammocks, catch up on sleep, and fill up on three big meals per day. A proper vacation!

Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

And I’m glad we did, because our final segment on the lake was far from our easiest.

To the headwaters

From Isla San Fernando, we paddled throughout the rest of the archipelago - an entirely unforgiving place for kayak landings. Then, from the eastern ‘shore’ of Isla la Venada, we made our final crossing to the small city of San Carlos, which guarded the headwaters of the Rio San Juan. Despite still being longer than anything I’d ever attempted back home, this crossing felt quite straightforward in comparison to the other long-hauls we’d done in days prior. But this crossing added new challenges as we were hit multiple times by short raging tropical rain storms which seemed to come out of nowhere. These threatened our visibility, made navigation very difficult, and soaked us to the bone. By the time we reached the waste-strewn concrete shores of the San Carlos port, we were very grateful to finally be done with this massive inland sea, and were looking forward to starting the final chapter down the river.

Above: Paddling into San Carlos and the headwater of the Rio San Juan. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: Paddling into San Carlos and the headwater of the Rio San Juan. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

San Carlos was a bit of a shock to the system after several days in relative isolation from urbanity. Loud, dirty, and swollen with rainwater, the city and its cobblestone streets seem to have changed little since its structures were first erected by Spanish conquistadors. The defensive battlements that were constructed to deter British aggression up the Rio San Juan are still in place, surrounded by cheaply constructed multi-story dwellings that often host business on the street level and residences above. The city playground was decorated for Christmas, and the waterfront plaza was alive with markets, music, and families. This was all a stark reminder that back home in Canada, my family was preparing for the holidays in the cold, snowy north. Meanwhile, I still had several days of paddling ahead - through the jungle, to the Caribbean.

Downstream we go...

Despite needing to paddle between 60-80km on any given day, we all expected the Rio San Juan to be the easiest paddling on the trip. Sure, we had to look out for crocodiles near the shoreline, and we needed to avoid being run down by boat traffic on the river. But we were told the currents would run at 5km/hr minimum, effectively doubling our typical pace on the lake.

This was not what we experienced upon launching into Rio San Juan on Day 9.

Instead of being carried along a conveyor belt by the current, we found ourselves being pushed back by strong easterly headwinds. This wind effectively negated the minimal flow that the river offered us, making it feel like we were still on the lake, still moving just 5km an hour. This was not going to be fast enough to reach our target destination before dark. So we were forced to dig in and paddle harder. Luckily our river guide, Matteo, knew each bend of the Rio San Juan, and was able to guide us in ways that balanced our protection from headwinds with our need to stay within the dominant flow of the current. This helped us pick up our pace significantly, eventually reaching close to 8km/hr in the final hours of the day, as the wind died and the sun sat low on the horizon.

Above: the village (and Spanish citadel) of El Castillo

Waterworld

With minutes to spare before nightfall, we managed to ferry across the river to the water-locked town of El Castillo. Situated on the southern shore of the San Juan, alongside a section of rapids they call El Diablo, this settlement felt like something out of Waterworld (except built alongside a river). Half of the dwellings and businesses sat on stilts embedded into torrential waters. Some were obviously sinking, others in the midst of constant repair. Half of the local children's park appeared to be submerged, guarded from the raging torrent by only a concrete wall. Supplied entirely by river boat, this town has been here since the Spanish built a defensive fort atop a nearby hill in the 17th-century to defend against pirates. Famous British naval figure Horatio ‘Hornblower’ Nelson led his first land battle victory at this fort when he was just 21 (though the entire expedition was eventually doomed by dysentery).

Speaking of dysentery… the San Juan is far from the clear, pristine rivers I’m spoiled to paddle in back home in rural Canada - and for understandable reasons. Mirky, silty, and brown, the San Juan is full of filth - from humans, cattle, and storm runoff from nearby settlements. Upon landing in El Castillo and taking a deep breath, it became evident to me that we had just paddled in via the region’s only sewage management system - the river itself. It was this realization that prompted me to start taking extra caution when snacking, though this turned out to be nearly impossible while paddling. My hands were always wet, constantly dipping in water ridden with bacteria and parasites, and yet all my snack food was finger food: crackers, cookies, trail mix, bars, fruit… hand to mouth, constantly. Even the mouth piece of my water bottle and hydration bladder was constantly being contaminated as I took waves on deck. All I could do was hope for the best. I needed the fuel.

Above: Jim Mee, owner and founder of Rat Race Adventure. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

From El Castillo, Day 10 gifted us a much swifter and narrower section of river that raised our spirits and set us up for our longest paddle of the trip. We decided to use this day to cover as much distance as possible, with the hopes of cutting a paddling day off the river segment and saving more time for our eventual, lengthy return. Maintaining between 8-10 km/hr, we followed our guide as the Rio San Juan transformed into the international border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

Crocs & AK-47s

Every 10-15 km or so, we’d prepare to pull off the river, check in at a manned military checkpoint, and submit our paperwork for review. Meanwhile, young men in fatigues and AK47s would silently stare at us with a mix of confusion and curiosity. A couple of times, we were searched and asked to put our cameras away, but these efforts by eager recruits were often cut short by more senior soldiers. We learned later that our lead guide from the lake segment - Laureano Mairena - had sent word ahead of us to ensure smooth passage for our group at each checkpoint. As the son of the revolutionary hero for whom that particular border patrol department is named after, Laureano certainly has some sway in these parts...

Each checkpoint stopover usually took around 10 minutes, offering us some of the only chances to get out of our kayaks via fixed docks to stretch, use the bathroom, and trade snacks. Our local guide, Matteo, was adamant about the risk of crocodiles, and strictly forbade us from exiting our kayaks mid stream or dangling our legs in the river. This ended up being tough for me, as my urinary tract was acting up and forcing me to pee every hour or so. But the more crocs we saw (and heard), the more seriously I heeded the warnings.

Eventually, I gave up trying to be decent, and got used to peeing straight into my cockpit or - once I was lucky to find one floating in the river - a spare plastic bottle. In fact, all of us eventually had to do this, and we all got used to sitting in our own urine and unleashing a wave of nausea each time we opened our spray decks. It was gross, but it was necessary to keep our legs on.

Above: a particularly serene section of the river, deep in a jungle valley. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: a particularly serene section of the river, deep in a jungle valley. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Several checkpoints later, after 80 km of paddling, we picked out an islet in the middle of the river to call home for the night. With sun was almost at the horizon, we were well situated to complete our journey the following day.

But the landing conditions here were some of the worst I’ve ever dealt with. No eddies to hide in, no respite for the current. No shallows, solid ground, or even strong foliage to hold onto. Just slippery, sketchy mud. Multiple team members ended up going for a swim on the pull out, but all the boats were lashed down tight to prevent anything from drifting away in the night.

And thank goodness for machetes! Matteo went in ahead to hack away at the jungle and clear ground for our camp. With the light fading fast, we each picked out a pair of trees, slung our hammocks and tarps, and prepared for another deluge of rain. I only stepped in one fire ant nest in the process of setting up my shelter in the dark. The holes in my water shoes were perfectly sized for them to get a few bites in. Ouch.

Darkness hits fast in the jungle, and so does fatigue. I boiled some water in my alcohol stove, warmed up one of my few prized dehydrated meals, and ate ravenously amidst the spiders and other creepy crawlies that come out at night. In contrast to the sweaty hostels of previous nights, my hammock felt like a true refuge - from the bugs, the rain, and the muscle fatigue that was gradually starting to settle in.

Above: Paddling in the jungle means perpetual wetness. Setting up camp in these conditions is extra fun. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: Paddling in the jungle means perpetual wetness. Setting up camp in these conditions is extra fun. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Our final day on the Rio San Juan was remarkable. Our goal was to reach Greytown - a historically British colonial settlement on the Caribbean coast - and complete our entire mission before nightfall. But with variable current and unknown conditions ahead, we really needed to maximize our time on the river. So we woke around 4am, still pitch dark and in the midst of a rain storm. Headlamps flashed in the darkness and we each struck camp and made our way to the water’s edge. Kayak reentry on that muddy shore was even trickier than the landing the night before, and one of us capsized in the process - but it was all laughs all ‘round. We started drifting downstream by 6am. The end was nigh, but we were still deep in it.

On our southeastern shore: Costa Rica. To the north: Nicaragua’s largest protected area; thick jungle, inhabited only on the shorelines by homesteaders raising small numbers of livestock, bananas, and other cash crops that could be traded downstream. Kids ran barefoot on the river’s shore, cheering and waving while their parents simply stopped their work and stared, seemingly bewildered as to why so many gringos were drifting past their homes. While it was not common to see river boats ferrying locals from their homes to nearby villages, we only saw a couple human powered vessels during the trip: small canoes with homemade paddles manned by fishermen who angled without rods. We were an anomaly, that’s for sure.

Above: My hands were starting to become perpetual pruned by this point.

Above: My hands were starting to become perpetual pruned by this point.

The Rio San Juan is one of those rare waterways that splits into two as it grows, one branch heading south into Costa Rica, the other carrying on eastwards toward the Caribbean Sea. From our final military checkpoint - just upstream from this split - we stuck to river-left to avoid missing our final ‘turnoff.’

At this point, the current began to slow once more, and the surrounding landscape flattened out. The tree line on the eastern shore began to thin. The air felt extra moist, and the scent of salt gradually crept into my nostrils. We could literally taste the end.

Near 3pm that day, with several miles still to go, we stopped at the shack of a local rancher who was a friend of our guide. We were blessed with a literal bucket full of fresh caught prawns from the nearby sea, boiled to perfection - with all the entrails still attached. Combined with a pot full of rice and some freshly made tomato salsa, this riverside feast was admittedly one of the tastiest meals of the trip, made all the better thanks to how tired and sore we all were.

Above: Finally, a proper lunch! An abandoned border checkpoint on the Costa Rican side of the San Juan. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Above: Finally, a proper lunch! An abandoned border checkpoint on the Costa Rican side of the San Juan. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

The Rio San Juan has long been used as a canal route connecting the sea to Lago Colcibolca, and our journey by kayak was no exception. But the end of the river still flattens into a maze of lagoons, many of them man-made to facilitate safe passage and connectivity to nearby villages. Dredging machines continue to work the river’s bottom, carving routes for larger, deeper vessels to take on their way upriver. Without our guide, Matteo, we might never have found our way through this maze.

By the time the sea was in sight, we were all going a bit crazy. Our route through the maze of lagoons had added multiple hours to our anticipated journey, and we were all hungry for our ‘summit.’ Our pace quickened in those final few kms, and soon we were all literally racing to the ‘finish line,’ desperate to call our coast-to-coast mission officially accomplished.

But I didn’t stop at the sand bar. I went straight out to sea. I wanted to feel the swell beneath my hull, to relish in the salt water once more. I put my paddle down, looked into the endless onslaught of breakers, and breathed a sigh of relief. And melancholy.

Before the rip current dragged me out to sea, I surfed one of those waves into shore, popped my skirt for the last time, and ran to meet my mates. Hugs and high fives all round. We had done it.

Our grand finale. From left to right: Kat, Caleb, Rick, Paul, Stuart, Budgie, James, Darren, Luke, Jim. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

Our grand finale. From left to right: Kat, Caleb, Rick, Paul, Stuart, Budgie, James, Darren, Luke, Jim. Photo Credits: James Appleton Photography | Rat Race Adventures

The End?

Finales like this are often bitter sweet. We anticipate ‘the end’ with gusto, only to get there and wish for ‘just a lil more.’ We return home to our comfort zone, only to relish in our lingering pain and soreness as a reminder of what we’ve done, what we’re capable of.

As it was a decade ago, a part of my spirit is still in Nicaragua.

And I can't wait go back with some friends - and my TRAK kayak - to reconnect with that part of myself, once again.

Aktie: